The Royal Navy worked to suppress the transatlantic slave trade after Britain abolished it in 1808. Sierra Leone (Freetown) became the main base for freed slaves and for the Vice-Admiralty Court that judged captured slave ships.

The Navy carried out patrols along the West African coast, intercepting slavers and freeing thousands of enslaved people. Ships like HMS Tartar and Thistle are noted for major captures. Britain also signed multiple treaties with Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, Brazil, and others, granting permission to stop and search vessels suspected of slave trading.

Important events include the 1816 Bombardment of Algiers to end Christian slavery, numerous ship captures in the 1820s, and laws like the 1824 Slave Trade Act that gave the Navy stronger enforcement powers. Despite disease, legal obstacles, and diplomatic disputes, the patrols significantly weakened the Atlantic slave trade.

This research highlights The Benin expedition and Britain’s transition from abolishing the slave trade to actively policing it at sea through treaties, naval action, and courts in Sierra Leone.

Benin Kingdom

In 1892, Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi of Benin signed a treaty with Britain in which he agreed to end both slave trading and the practice of human sacrifice. This took place during the period of British anti-slavery efforts. although Ovonramwen made these promises, there is serious doubt whether he would have been able to fulfill them even if he wanted to.

In 1894, a British naval force attacked and captured the town of Brohemie on the Benin River. The reason was that Brohemie’s chief had been involved in the slave trade. When the naval force arrived, they discovered large quantities of goods in his stronghold: 7,000 cases of gin and 600 cases of tobacco, indicating wealth derived from the slave trade.

After the attack, the chief fled to Lagos. He was later put on trial and exiled for his involvement in the slave trading activities. Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi of Benin is named in the account, placing the event within the broader context of British anti-slavery patrols and the relationship between Benin’s rulers and British colonial interference during that period.

In 1896, James Phillips wrote to the Foreign Office reporting that the King (Oba) of Benin was deliberately obstructing trade and preventing the government from “opening up” the country by using a fetish, specifically placing a juju on palm kernels, the area’s most profitable product, and enforcing the ban under threat of death. He said the Oba had closed the markets and only reopened them intermittently in response to presents from the Jakri (Itsekiri) chiefs, which Phillips had advised the chiefs to stop giving.

Phillips requested permission to visit Benin City in February to depose and remove the King, establish a native council in his place, and take further measures needed to open the country. He asked for a substantial armed force to prevent danger: 250 troops, two seven-pounder guns, one Maxim gun, one rocket apparatus from the Niger Coast Protectorate Force, plus a detachment of 150 Lagos Hausas, and sought sanction from the Secretary of State for the Colonies to use colonial forces to that extent. He anticipated little popular resistance but noted a hope that ivory found in the King’s house might cover the costs of removing the Oba.

on 5 January 1897 ,The Benin Massacre recounts the ambush of a British delegation led by James Phillips near Benin, in present-day Nigeria. The party, which included Major Copeland-Crawford, Dr. Elliot, Captain Malinger, Gordon, and others, was attacked by Benin forces. Most of the Europeans were killed, including Phillips and Copeland-Crawford, while Campbell was captured but later executed after the Oba of Benin refused him entry to the city.

Only a handful of survivors escaped, with one porter later carrying news of the massacre back to the coast. The event, in which nearly all the porters were also slain, became the immediate trigger for the Benin Punitive Expedition of 1897, during which British forces invaded and sacked Benin City, deposed the Oba, and brought the kingdom under colonial control.

THE HORRORS OF BENIN CITY (Illustrated London News, 27th March 1897)

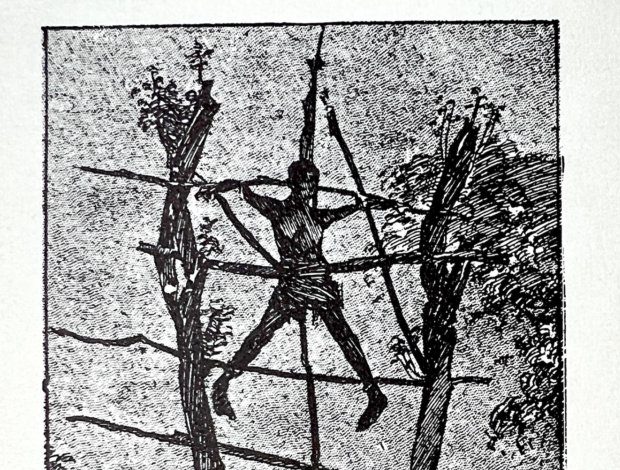

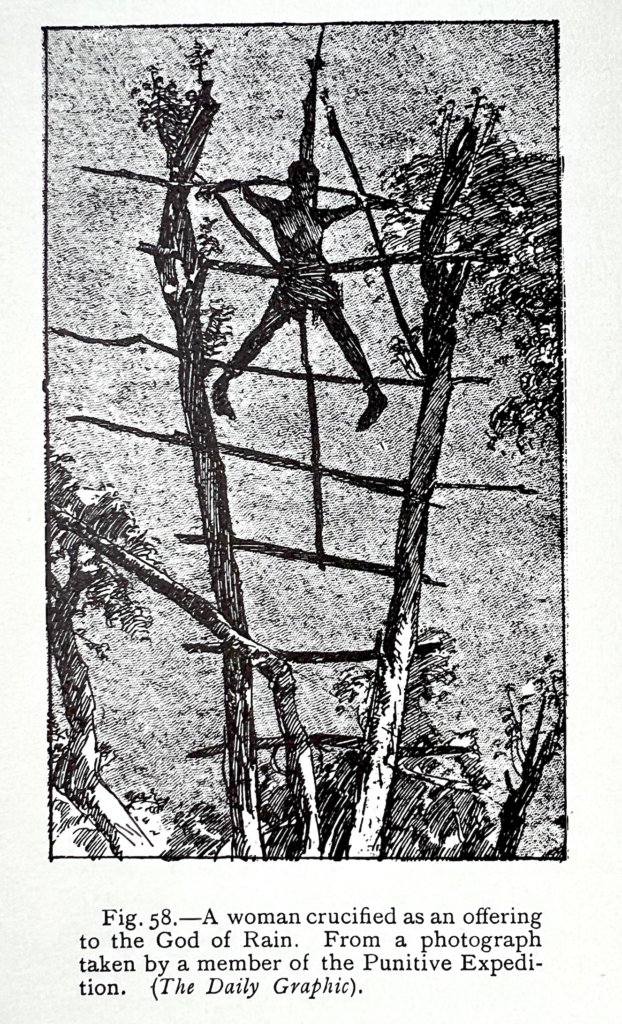

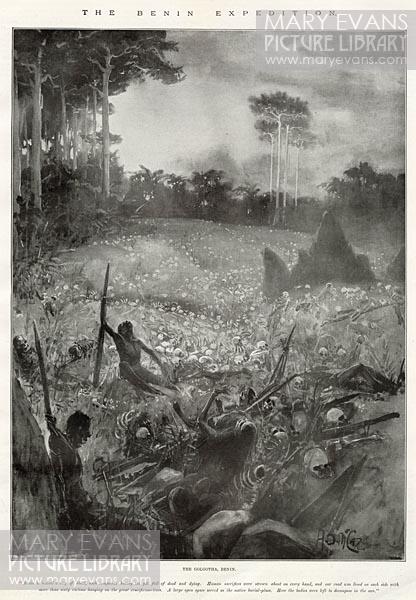

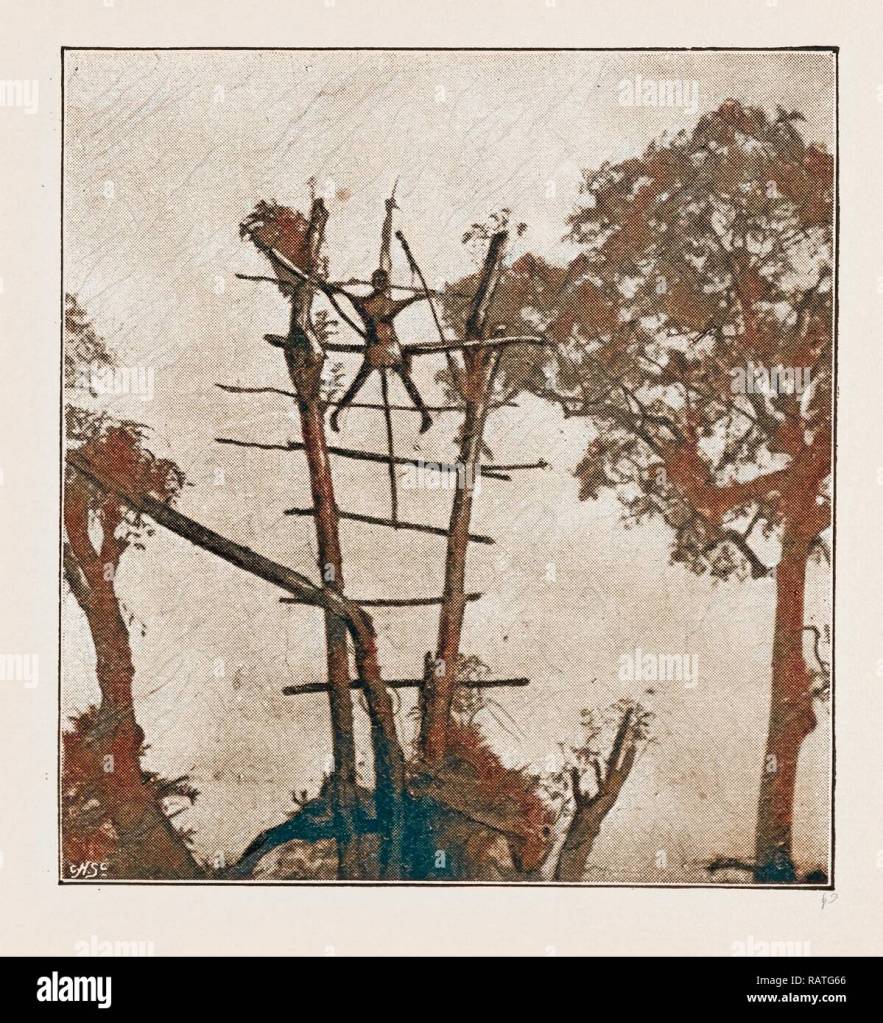

Benin is indeed a city of blood, each compound having its pit full of dead and dying; human sacrifices were strewn about every hand, hardly a thing was without a red stain, and one road was lined on each side with more than sixty victims. The city consists of a number of huge compounds of oblong shape surround by walls made of red mud, about nine inches thick, and of extraordinary strength. At the top of these compounds there was usually a covered space, the ground underneath being raised about two feet. Here the people of Benin hold their hideous rites to their gods of fetishes, which are ranged along the wall, and which comprise elephants’ tusks and carved figures of ivory, brass, and bronze, having the most grotesque appearance. In the centre of the sheltered part was an orifice, from the sides of which blood was streaming. I must not omit mention the huge crucifixion trees which were in the wide road leading past the compounds, and on which the remains of victims could still be seen. Near these were more pis full of bodies, and from one moans could be heard. Some of the corpses were hoisted out, and a boy who had been Gordon’s native servant was rescued. He had been for over five days in this pit, covered by a heap of dead and dying, who had been thrown in after him. From another pit a woman and two boys were rescued, but although every attention has been paid to them, I am afraid little hope can be entertained of their ultimate recovery. In the King’s palaver-house the whole of the effects taken from the murdered whites was found almost untouched, their sporting guns, their helmet-cases, and cameras, and the merchandise brought by the trades of the expedition.

THE GOLGOTHA, BENIN (Illustrated London News, 27th March 1897)

Source: The blue jackets – https://www.thebluejackets.co.uk/research