The UK’s prolonged cost-of-living crisis is increasingly reshaping public attitudes toward institutions once seen as stable pillars of national life. As households struggle with rising prices, stagnant wages, and declining living standards, trust in government, regulators, and economic institutions is showing visible strain.

Over the past few years, the cost of essentials such as housing, energy, food, and transport has risen sharply. Rent and mortgage payments now consume a disproportionate share of household income, while food inflation has forced many families to cut back on both quantity and quality of meals. Energy costs, despite recent stabilisation, remain significantly higher than pre-crisis levels, leaving millions anxious about future price shocks.

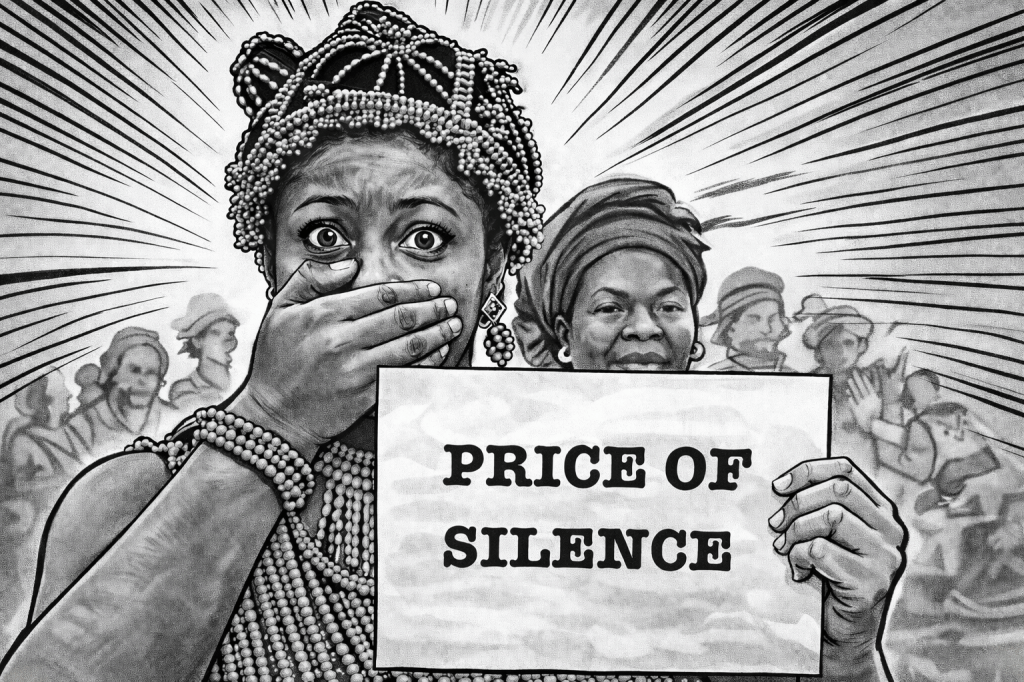

For many Britons, the issue is not only the rising cost itself but the perception that institutions have failed to protect them. Successive policy interventions — from energy price caps to temporary tax reliefs — are widely viewed as reactive, insufficient, or poorly targeted. This has fed a sense that economic management is disconnected from everyday realities, particularly for low- and middle-income households.

Distrust has also been amplified by widening inequality. While wages for many workers have struggled to keep pace with inflation, corporate profits in sectors such as energy, finance, and food retail have remained strong. The contrast between record profits and declining living standards has reinforced beliefs that the economic system favours large corporations and asset owners over ordinary citizens. Regulatory bodies, tasked with ensuring fairness and competition, are increasingly seen as ineffective or overly accommodating.

Public confidence in political leadership has similarly eroded. Frequent changes in fiscal policy, shifting narratives around responsibility for inflation, and highly publicised policy reversals have contributed to perceptions of instability and incompetence. Opinion polling consistently shows low trust in politicians to manage the economy, with many people believing that decisions are driven by short-term political survival rather than long-term public interest.

The strain has extended beyond government to other institutions. Local councils, under financial pressure, have reduced services or raised council tax, deepening frustration at the local level. The financial sector, while essential to the UK economy, is often viewed as detached from the hardships facing households, particularly given the legacy of past crises and bailouts.

This erosion of trust has tangible social consequences. Growing numbers of people are disengaging from formal politics, while others are turning to protest, strikes, or alternative sources of information and support. Trade union activity has increased, and grassroots mutual aid networks have expanded, reflecting both dissatisfaction with institutional responses and a desire for community-based solutions.

Experts warn that sustained distrust poses long-term risks. Institutions rely on public confidence to function effectively, particularly during periods of economic stress. Without trust, policy measures are less likely to gain public support, compliance weakens, and social cohesion can fray.

While the cost-of-living crisis has global roots, its domestic impact is forcing a reckoning in the UK. Addressing rising prices alone may not be enough to restore confidence. Analysts argue that rebuilding trust will require clearer accountability, more transparent decision-making, and policies that visibly improve everyday living conditions rather than abstract economic indicators.

As the crisis continues to shape public life, the challenge facing UK institutions is no longer just economic management, but credibility. Whether they can regain the confidence of a population under sustained financial pressure may prove decisive for the country’s social and political stability in the years ahead.