Public skepticism toward cancel culture is rising in both the United States and the United Kingdom, as debates over free speech, accountability, and social justice grow more complex. What began as a tool for marginalized voices to call out abuse and discrimination is now increasingly questioned for its perceived excesses, unintended consequences, and impact on democratic discourse.

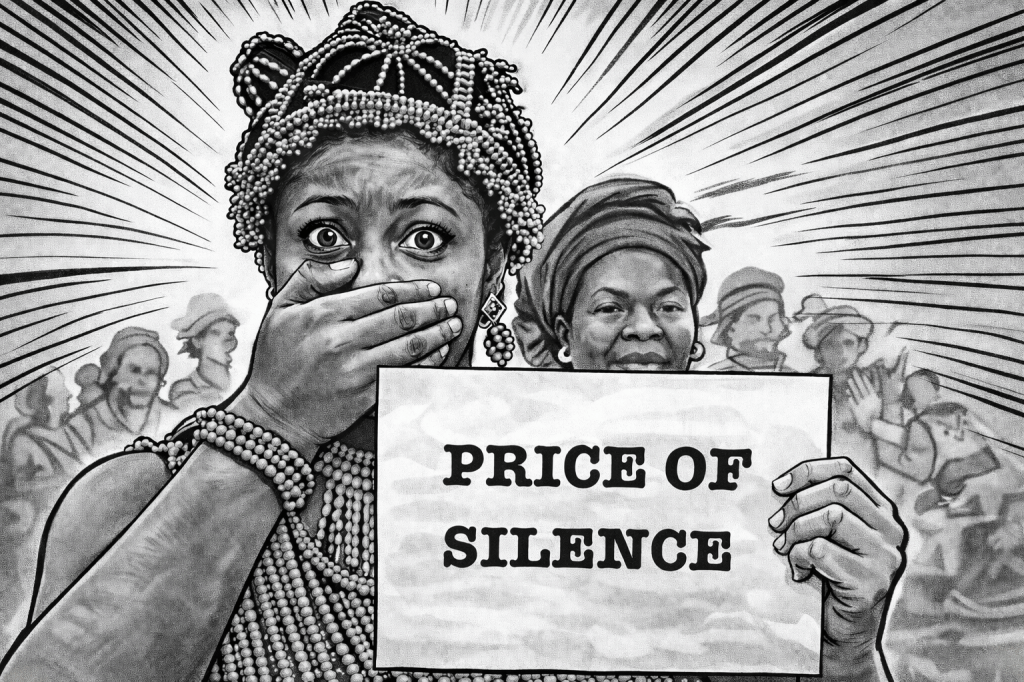

In the United States, cancel culture has become deeply entangled with politics, media, and corporate life. High-profile cases involving entertainers, academics, journalists, and public officials have turned social media into a powerful court of public opinion. Critics argue that online outrage often moves faster than due process, leading to professional and reputational damage without clear standards for evidence, context, or redemption. While supporters see cancellation as a form of accountability in a system that often protects the powerful, skeptics warn that it can encourage fear, self-censorship, and ideological conformity.

The American debate is sharpened by the country’s strong free speech tradition. Universities, once viewed as spaces for open debate, have become flashpoints, with speakers disinvited and staff disciplined following online campaigns. Polling in the US suggests a growing number of people believe cancel culture has gone too far, even among those who support social justice goals. This tension reflects a broader cultural divide between calls for social responsibility and concerns about freedom of expression.

In the UK, cancel culture skepticism has taken a different but related form. British debates tend to be less polarized but more focused on institutional overreach and cultural authority. Controversies surrounding comedians, writers, museum curators, and broadcasters have sparked questions about who gets to define acceptable speech and values in a plural society. Critics argue that informal social sanctions, when amplified by institutions such as employers or cultural bodies, can function as de facto censorship without legal oversight.

The UK case also highlights class and power dynamics. Skeptics point out that cancel culture often affects individuals without significant institutional protection, while powerful figures are more likely to recover or remain insulated. This has led to accusations that cancellation is unevenly applied, shaped by media attention and public sentiment rather than consistent ethical standards.

Across both countries, distrust in social media platforms plays a central role. Algorithms that reward outrage and rapid judgment are seen as intensifying cancel culture dynamics. What might once have been a localized dispute can quickly escalate into global condemnation, leaving little room for nuance, apology, or learning. Critics argue that this environment discourages open conversation and replaces debate with moral absolutism.

At the same time, skepticism does not necessarily translate into a rejection of accountability. Many critics of cancel culture distinguish between legitimate criticism and what they view as punitive pile-ons. They argue for alternative approaches that emphasize proportionality, restorative justice, and the possibility of change rather than permanent exclusion.

The growing unease in both the US and UK reflects a broader cultural reckoning. As societies grapple with inequality, historical injustice, and rapidly changing norms, the question is not whether people should be held accountable, but how. Cancel culture skepticism signals a desire to balance social responsibility with fairness, dialogue, and democratic values.

As public opinion continues to evolve, the debates unfolding in America and Britain suggest that the future of accountability may depend less on mass condemnation and more on transparent processes that allow for critique, context, and rehabilitation.