The growing call to centre African epistemology over Western academic models reflects a broader struggle over knowledge, power, and cultural legitimacy. For centuries, African ways of knowing have been marginalised, dismissed as informal, or excluded entirely from dominant academic frameworks shaped by European history, Enlightenment rationality, and colonial expansion. Today, scholars, artists, and activists are increasingly challenging this hierarchy, arguing that African epistemologies are not alternative supplements but complete systems of knowledge in their own right.

Western academic models tend to prioritise written texts, linear logic, individual authorship, and universal claims to objectivity. Knowledge is often validated through formal institutions such as universities, peer-reviewed journals, and standardized methodologies. While these systems have produced important scientific and theoretical advances, they also carry cultural assumptions rooted in European experience. When applied globally, they frequently overlook context, relationality, spirituality, and communal knowledge systems that do not fit their criteria.

African epistemology operates differently. Knowledge is often embedded in oral traditions, proverbs, rituals, performance, and everyday practice. Truth is not always abstract or universal, but situational, relational, and responsive to community needs. Elders, storytellers, healers, and artisans function as knowledge holders, transmitting understanding across generations through lived experience rather than formal documentation. In this framework, knowing is inseparable from being and doing.

Time is another point of divergence. Western academic models often treat knowledge as progressive and accumulative, moving toward mastery and control. African epistemologies frequently understand time as cyclical, ancestral, and layered, where past, present, and future coexist. Knowledge is preserved not to dominate nature or society, but to maintain balance, continuity, and ethical relationships between people, land, and the spiritual realm.

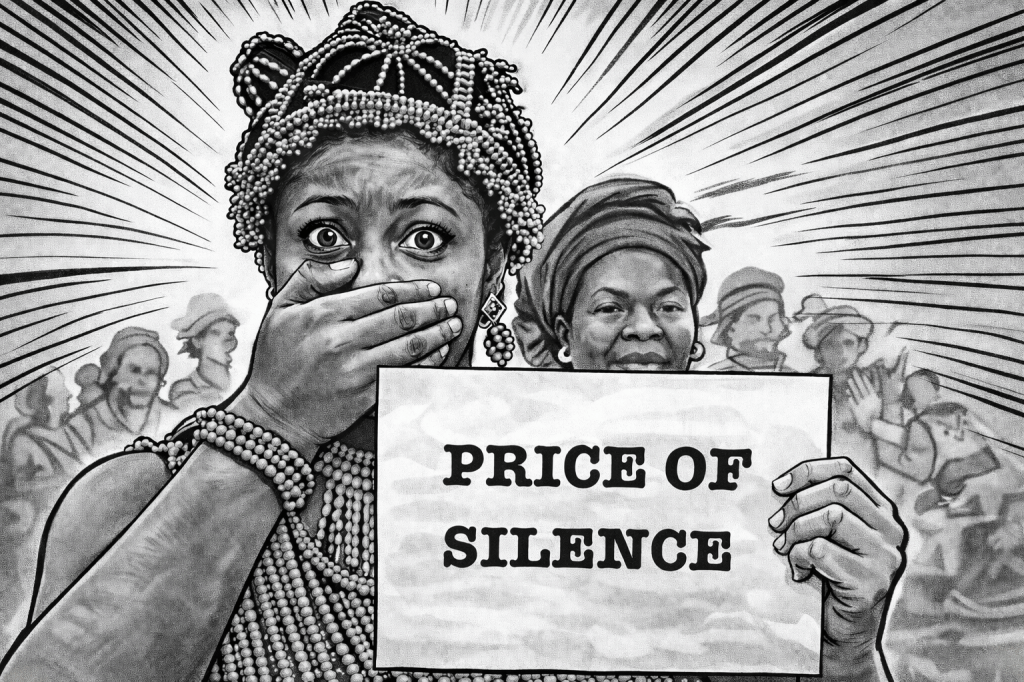

The privileging of Western models has had tangible consequences. Colonial education systems systematically devalued African languages, histories, and sciences, replacing them with European curricula presented as universal. This produced generations trained to view their own cultural knowledge as inferior or irrelevant. Even today, African scholars are often required to frame research through Western theories to gain academic legitimacy, reinforcing epistemic dependency.

Placing African epistemology at the centre does not mean rejecting Western knowledge outright. Rather, it calls for epistemic plurality and intellectual sovereignty. It insists that African societies should define research questions, methods, and validation criteria according to their own realities. For example, indigenous agricultural knowledge, traditional conflict resolution systems, and community-based health practices offer insights that Western frameworks may fail to recognise or measure effectively.

This shift also challenges the separation between academia and everyday life. African epistemology resists the idea that knowledge belongs only to experts or institutions. It affirms that wisdom emerges from collective experience, social responsibility, and ethical conduct. Knowledge is judged not only by accuracy, but by its ability to sustain life, dignity, and harmony.

In contemporary contexts, this debate extends into art, philosophy, technology, and governance. Digital archiving of oral histories, the revival of indigenous languages in scholarship, and the recognition of African philosophy as philosophy rather than folklore are all part of a wider epistemic rebalancing. These efforts confront the lingering effects of colonialism at the level of thought itself.

Ultimately, prioritising African epistemology over Western academic models is about reclaiming authority over meaning. It is a refusal to accept that valid knowledge must pass through Western filters to be considered legitimate. By centring African ways of knowing, societies assert that their histories, experiences, and intellectual traditions are sufficient foundations for understanding the world and shaping the future.