For much of the world, Christmas has become synonymous with a single figure: Santa Claus. Red-suited, benevolent, and commercialised, he dominates global imagery of the season. Yet this version of Christmas is not universal, nor is it historically inevitable. Beyond Western traditions lies a wide range of cultural, spiritual, and symbolic interpretations of the season, many of which predate or exist entirely outside the Santa narrative. Exploring these alternatives reveals how deeply cultural power shapes what is considered “normal” or “traditional.”

The modern image of Santa Claus is a product of European folklore, Christian reinterpretation, and 19th–20th century commercialisation, particularly through American media. Over time, this image was globalised through advertising, film, and consumer culture, often displacing local traditions. In many non-Western contexts, Christmas arrived not as a neutral celebration but as part of colonial and missionary projects that reshaped indigenous belief systems and seasonal rituals.

Across Africa, for instance, precolonial societies already marked seasonal cycles through harvest festivals, ancestral commemorations, and communal rites tied to the land. These celebrations emphasised continuity, gratitude, and collective responsibility rather than gift-giving or commercial exchange. In many places, Christianity layered itself onto these existing rhythms, but the imported imagery of Santa remained culturally distant, sometimes adopted superficially while deeper traditions persisted underneath.

In parts of Asia, Christmas is often celebrated as a social or romantic event rather than a religious one. In Japan, for example, it is associated with illumination displays, commercial festivity, and communal gatherings rather than Christian mythology. The figure of Santa exists, but stripped of spiritual meaning, functioning more as a symbol of seasonal joy than a religious or moral authority.

Indigenous cultures around the world have long marked the winter season through solstice observances, honoring cycles of death and renewal rather than focusing on gift-bringers. These traditions frame winter as a time of reflection, rest, and spiritual balance, contrasting sharply with the consumption-driven narrative dominant in Western media. The re-emergence of these practices reflects a broader desire to reconnect with land-based cosmologies rather than imported myths.

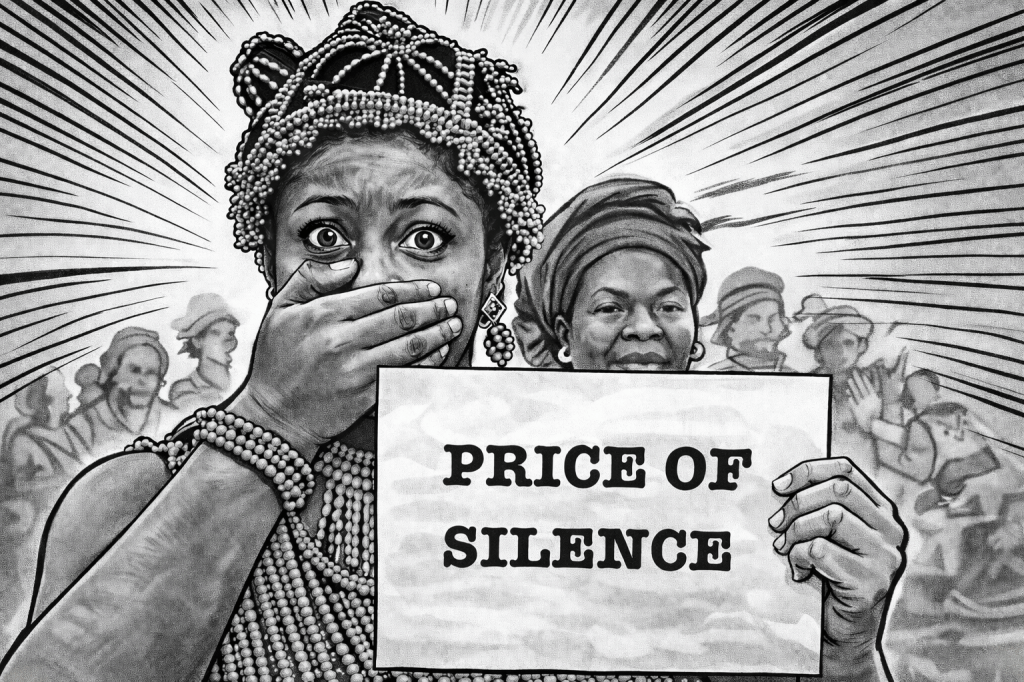

Rejecting Santa as the central symbol of Christmas does not mean rejecting celebration itself. Instead, it opens space for alternative narratives rooted in local history, spirituality, and community values. It challenges the idea that joy must be mediated through consumption or a single global icon. For many, this reclamation becomes an act of cultural autonomy, resisting the homogenisation of global culture.

In recent years, artists, educators, and communities have begun reimagining Christmas through indigenous, diasporic, and Afrocentric lenses. Storytelling, ancestral remembrance, communal meals, and acts of collective care replace the transactional logic of gift exchange. The season becomes less about fantasy figures and more about lived relationships.

Ultimately, exploring Christmas without Santa is not about rejection but expansion. It invites a broader understanding of how societies mark time, meaning, and togetherness. By acknowledging multiple narratives, we move toward a more inclusive cultural imagination—one that recognises that celebration does not require uniform symbols, and that tradition is richest when it reflects the diversity of human experience.