Across Nigeria, traditional institutions continue to occupy a complicated space between history, power and modern governance. While kings, emirs and sultans officially operate under the authority of state governments and can be appointed or removed through political processes, their real influence often stretches far beyond paperwork and protocol. In many communities, these royal figures still command deep loyalty, cultural reverence and social authority that no elected official can easily replicate.

Legally, traditional rulers exist at the mercy of state governments. Governors issue their staffs of office, approve their recognition and, in some cases, have the power to depose them. On paper, this places monarchs firmly beneath the modern political structure. In practice, however, the story is far more layered. Across the country, many traditional rulers continue to shape public opinion, influence local politics, mediate disputes and act as power brokers between the people and the state.

This enduring influence raises an important question: is the continued power of traditional institutions a strength or a setback in Nigeria’s democratic evolution?

Supporters argue that traditional rulers remain vital stabilising forces, especially in communities where trust in formal political institutions is low. They provide cultural continuity, command respect across generations and often act as first responders in conflict resolution. In rural and semi urban areas, their word still carries more weight than that of elected officials, making them essential to community cohesion.

A widely cited example is the Ooni of Ife, whose leadership has extended beyond ceremonial duties into cultural diplomacy, youth engagement and economic development. Through investments in cultural tourism, technology hubs, and diaspora engagement, the Ooni has positioned his role as a bridge between heritage and modern development. His efforts to promote unity among Yoruba communities at home and abroad have earned him admiration, particularly among young people seeking a sense of identity rooted in tradition but open to innovation.

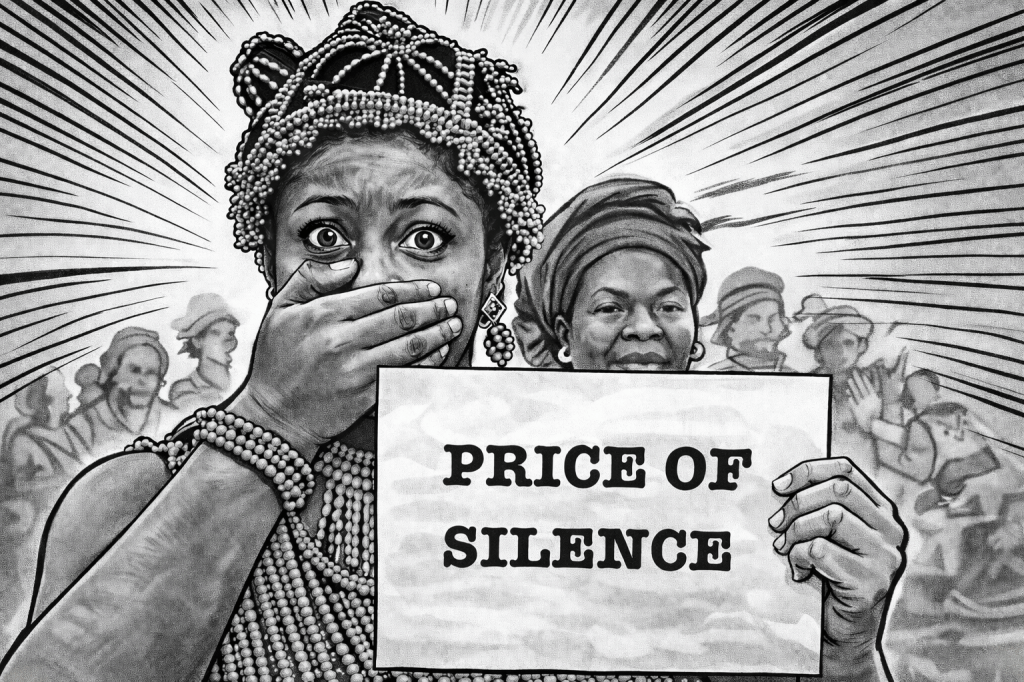

Yet this is not the full picture across the country. In other regions, the influence of traditional rulers has become more controversial. Some have been accused of deepening political divisions, aligning too closely with partisan interests, or using cultural authority to silence dissent. In these cases, royal influence has not united communities but sharpened existing fractures, raising questions about accountability and relevance in a democratic society.

The contrast reveals a central tension in Nigeria’s evolving political culture. Traditional power can either complement modern governance or undermine it, depending on how it is exercised. Where monarchs use their influence to promote dialogue, development and unity, they often earn legitimacy beyond ceremonial status. Where power is used to entrench personal interests or inflame local rivalries, it reinforces arguments that traditional institutions should have a more limited role.

As Nigeria continues to negotiate its identity between inherited traditions and democratic ideals, the place of its kings, emirs and sultans remains deeply contested. What is clear is that their influence has not faded. Whether that influence becomes a force for collective progress or continued division depends largely on how responsibly it is wielded, and how willing both the state and the people are to demand accountability from those who still command the deepest cultural loyalties.