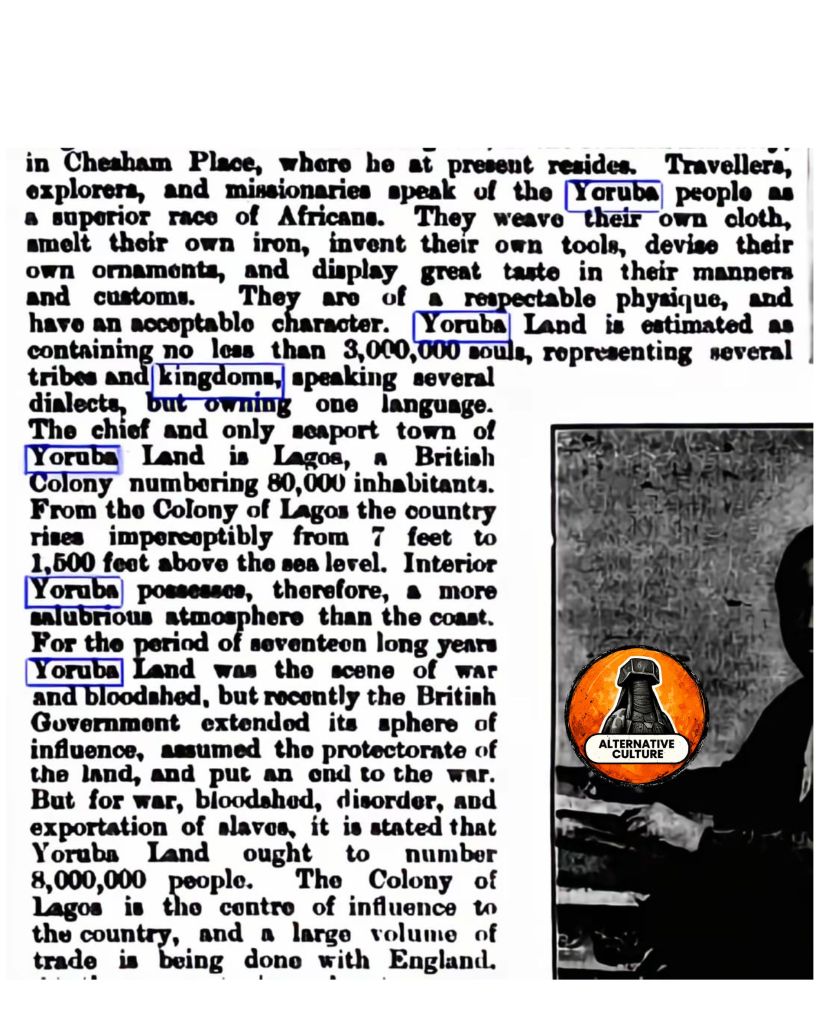

In September 1895, the British newspaper The Colonies and India published an article that stood out sharply against the dominant racial attitudes of the colonial era. Drawing on the observations of travellers, explorers, and missionaries, the paper described the Yoruba people of West Africa as a “superior race of Africans.” While the language reflects the racial hierarchies of nineteenth-century Europe, the reasons given for this description reveal a society whose level of organisation, skill, and cultural refinement challenged prevailing imperial assumptions about Africa.

According to the report, the Yoruba were distinguished by their technological self-sufficiency. They were said to weave their own cloth, smelt their own iron, and invent their own tools, demonstrating control over essential industries rather than reliance on external production. They also devised their own ornaments, indicating a strong aesthetic tradition alongside practical skill. For European observers accustomed to framing African societies as dependent or technologically undeveloped, this level of internal production marked the Yoruba as exceptional.

The newspaper further noted that the Yoruba displayed great taste in their manners and customs. Their social behaviour, physical bearing, and character were described as respectable and acceptable by contemporary European standards. Such remarks were significant in an era when African cultures were often dismissed as lacking refinement or moral order. The recognition of structured customs and social discipline suggested a society governed by established norms and values rather than disorder.

The article also highlighted the political and linguistic cohesion of Yoruba Land. It was described as containing no fewer than three million people, organised into several tribes and kingdoms, speaking multiple dialects while sharing a single language. This combination of diversity and unity pointed to a complex social structure capable of sustaining large populations across expansive territory. The existence of multiple kingdoms implied established systems of governance long before colonial intervention.

Lagos was identified as the chief and only seaport town of Yoruba Land and described as a British colony with approximately eighty thousand inhabitants at the time. From Lagos, the land was said to rise gradually from the coast to higher elevations inland, creating a healthier climate away from the shoreline. The interior of Yoruba Land was therefore regarded as particularly suitable for settlement, reinforcing the perception of a well-situated and viable civilisation.

Despite its admiration, the article reflected the contradictions of colonial thinking. It acknowledged that for seventeen years Yoruba Land had been affected by war and bloodshed, yet it framed British intervention as the force that ended conflict by extending imperial influence and assuming a protectorate. At the same time, the paper admitted that without war, disorder, and the exportation of enslaved people, the population of Yoruba Land might have reached eight million. This recognition implicitly acknowledged the destructive impact of both regional conflict and external interference.

Viewed today, the 1895 article is revealing not because it labels the Yoruba as “superior,” but because it documents the qualities that made such a label possible within a colonial publication. The Yoruba were recognised as industrious, technologically capable, culturally refined, politically organised, and economically active. These observations, filtered through the biases of empire, nevertheless offer a historical record of a sophisticated African civilisation that contradicted the myths used to justify colonial domination.

Rather than endorsing the racial language of the period, the article can now be read as unintended evidence of Yoruba achievement. It affirms that long before colonial rule, Yoruba society possessed the skills, structures, and cultural depth that Europeans themselves associated with advancement and civilisation.