The Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) in Benin City has emerged as one of Nigeria’s most ambitious cultural projects of recent years. Founded in 2020 as an independent non-profit institution, its mission is to preserve, celebrate and expand knowledge of West African arts and culture through research, education, conservation and artistic engagement. The museum’s campus includes research facilities, public spaces and exhibition areas designed to connect heritage with contemporary creativity across the region.

During the private preview of MOWAA’s inaugural exhibition Nigeria Imaginary: Homecoming in November 2025, visitors encountered a remarkable range of historical and artistic works, including Nok terracotta, Ife bronze heads, Igbo-Ukwu artefacts and the celebrated Owo leopard. These objects illustrate deep artistic traditions that span centuries and remind viewers that West African cultural production was complex, interconnected and regionally diverse long before colonial disruption.

Amid this moment of cultural celebration, however, controversy erupted. Protesters disrupted the event, asserting that the museum should instead be named a Benin Royal Museum and reflecting tensions over claims to cultural authority, restitution and custodianship of historic works that have been looted and dispersed abroad. Some of the unrest was tied to disputes over recently returned Benin Bronzes, which are not currently exhibited at MOWAA due to ongoing legal and custodial disagreements involving traditional authorities and government bodies.

Central to this debate is the question of identity and purpose. Some stakeholders have argued that the museum should be focused primarily on Benin royal art, but this approach overlooks a key fact: the works featured in MOWAA’s early exhibitions and archive are drawn from across West Africa and are not limited to the Benin Kingdom alone. The Owo leopard, for example, comes from the historic Owo Kingdom, whose artistic traditions have often been overshadowed or misattributed within broader narratives of ‘Benin art.’

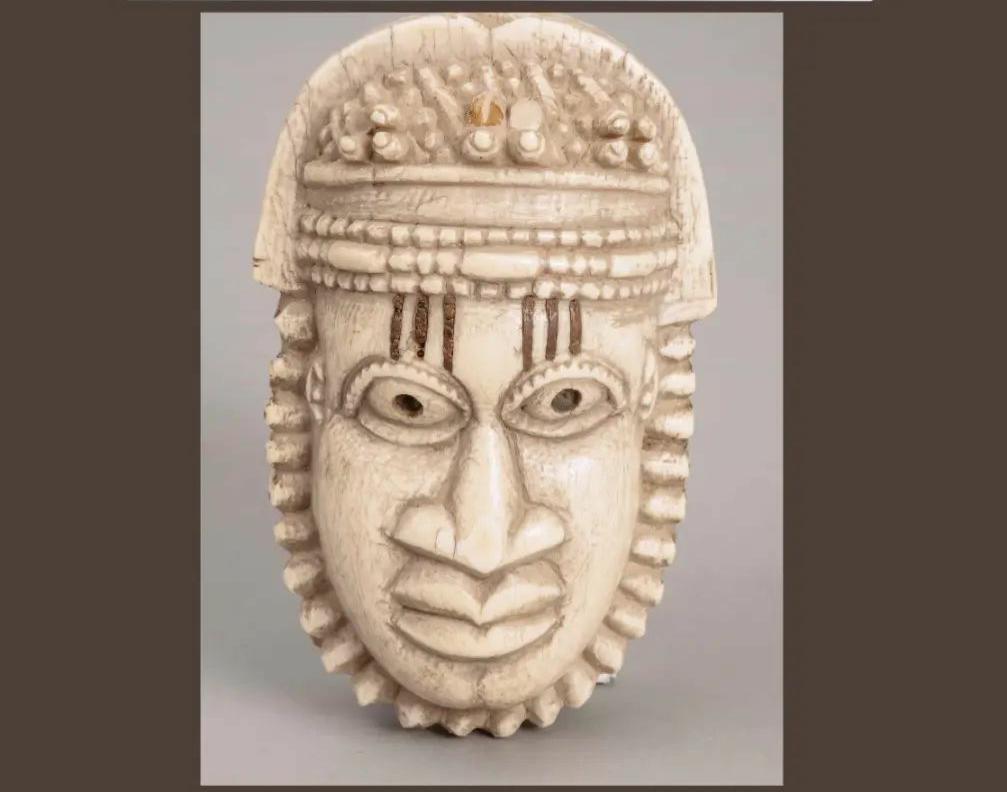

For generations, many Owo artefacts were either incorrectly attributed to the Benin Kingdom or subsumed under a generic label of Benin ivory and bronzes in Western collections. This erasure of distinct artistic identities has diminished recognition of Owo’s unique contributions to the region’s visual history. If MOWAA is to be true to its mission as a museum of West African art, it must ensure that Owo works and other historically significant traditions are properly researched, contextualised and credited for their origins. The museum’s mandate is to reflect the full richness of the region’s cultural tapestry, not to prioritise one lineage at the expense of others.

Retaining the name Museum of West African Art thus holds symbolic and practical importance. A broader institutional identity allows the museum to embrace a wide range of artistic practices, ancient, historical, and contemporary, from across the region, including but not limited to Benin, Owo, Ife, Nok, Igbo-Ukwu and beyond. A narrower title such as Benin Royal Museum could constrain the institution’s scope, risk reinforcing the very silos that colonial histories helped create, and diminish opportunities for inclusive research, collaboration and cultural exchange.

Properly representing the Owo Kingdom’s artistic legacy at MOWAA is not merely an act of historical correction; it is a step toward restoring respect for the diverse voices that make up West Africa’s cultural heritage. As the museum develops its programmes, exhibitions and educational outreach, it has the opportunity to foster nuanced understandings of the region’s past and to challenge longstanding misattributions that have impoverished global perspectives on African art.

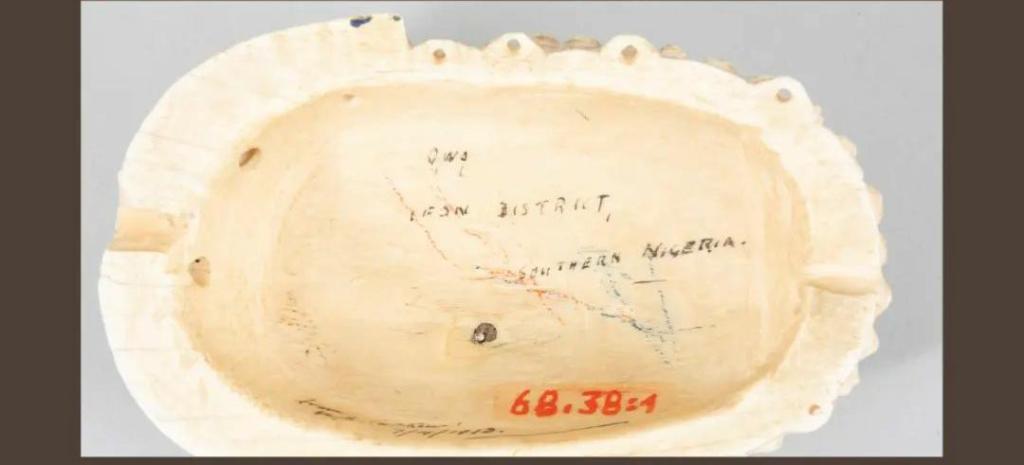

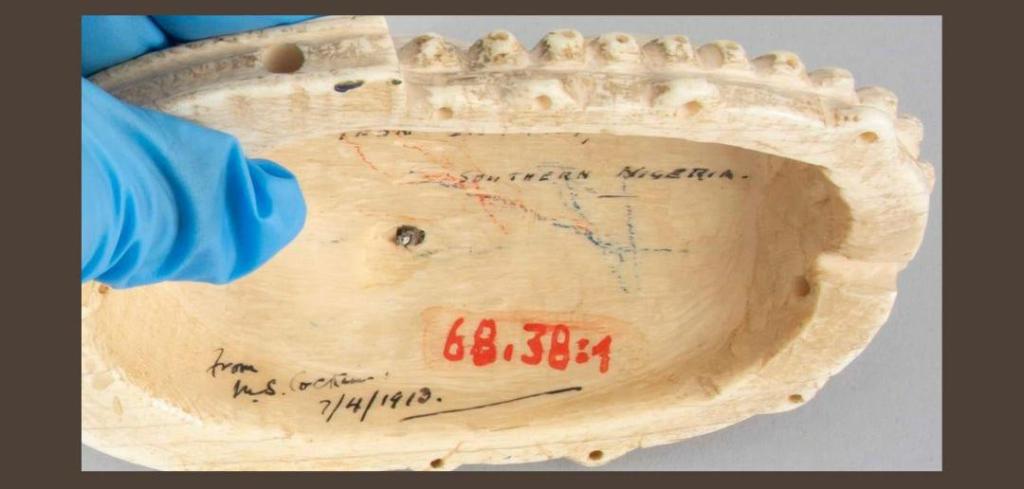

This Owo ivory mask pendant, carved in the 1800s, represents the head of a king. For many years, this artwork was wrongly attributed to Benin artefacts in Western museums.

In a world where museum narratives shape both national identity and international perceptions, MOWAA’s commitment to a genuinely West African framework can foster unity rather than division. By foregrounding accurate attribution and contextual scholarship, and by honouring the distinct legacies of kingdoms such as Owo alongside Benin and others, the museum can embody its founding vision: celebrating the diversity, resilience and creativity of West African cultures on their own terms.