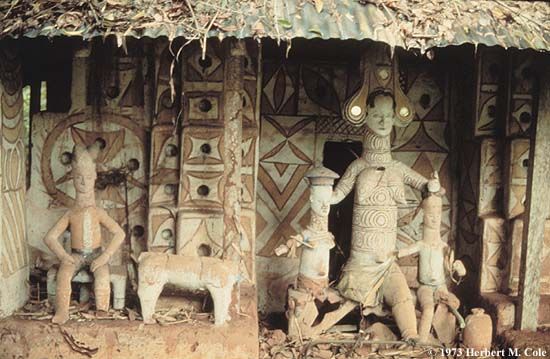

Across Africa, sacred sites and ancestral shrines continue to exist quietly within villages, towns, forests, courtyards, and family compounds. Many of these shrines are modest in size, sometimes no more than a small structure of clay, wood, stone, or earth. To the untrained or biased eye, this physical modesty has often been misinterpreted as a sign of underdevelopment, primitiveness, or spiritual inferiority when compared to the grand cathedrals, basilicas, and monumental religious architecture of Europe. This interpretation is not only inaccurate, it fundamentally misunderstands African spirituality, African cosmology, and African conceptions of the divine.

The difference between African sacred spaces and European religious monuments is not a question of capacity, intelligence, or technological limitation. It is a difference rooted in worldview.

In many African spiritual systems, ancestral worship is central. Ancestors are not abstract, distant, or omnipotent gods removed from human experience. They are people who once lived, walked the earth, built families, farmed land, fought wars, told stories, and died. They are remembered not as supreme beings demanding awe through architectural dominance, but as elders whose presence continues through lineage, land, memory, and ritual. Because ancestors are buried in the earth, African shrines often emerge from the ground itself. The earth is not merely a physical surface; it is sacred, alive, and ancestral. A small shrine, low to the ground, is therefore not a sign of spiritual weakness but a deliberate symbolic choice that reflects proximity, intimacy, and continuity between the living and the dead.

By contrast, in European Christianity, God is conceptualised as a singular, almighty, transcendent being who exists far above human existence. The cathedral, with its soaring ceilings, towering spires, stained glass, and monumental scale, reflects a theology that emphasises distance, power, and transcendence. The architecture mirrors the belief system. A “big God” requires a “big house.” African spirituality does not operate within this framework. Ancestors do not need to be elevated above humanity because they are humanity, remembered and revered. They are not worshipped for domination, but honoured for guidance, protection, and moral continuity.

If African societies wished to build vast temples or monumental worship halls, they could and did. The ancient stone cities of Great Zimbabwe, the monumental earthworks of Sungbo’s Eredo, the sacred urban planning of Ile-Ife, the palace complexes of Benin, and the advanced city-states of the Sahel all demonstrate architectural sophistication. The absence of gigantic shrines in many African spiritual traditions is not a failure of imagination or skill, but a conscious reflection of spiritual philosophy. African development historically focused on what communities needed socially, spiritually, and environmentally, not on excess or symbolic domination.

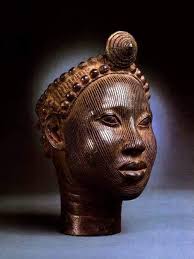

This misunderstanding of African spirituality is deeply connected to how the West has historically attempted to diminish African contributions to global development. African art provides one of the clearest examples of this pattern. When Europeans first encountered the bronze heads of Ife and the Benin Bronzes, they refused to believe Africans could have produced such works. Early European scholars absurdly suggested that the artefacts must have been made by lost white civilisations, Portuguese traders, or even the mythical city of Atlantis. The idea that Yoruba and Edo peoples possessed the metallurgical knowledge, artistic philosophy, and technical precision to create such works was inconceivable to colonial minds shaped by racial hierarchy.

Yet archaeological and historical evidence confirms that African societies were working with iron long before the so-called European Bronze Age was formally recognised. African metallurgy was not derivative; it was indigenous, innovative, and deeply integrated into social and spiritual life. Iron was not just a material but a sacred substance associated with deities such as Ogun among the Yoruba. Bronze, brass, clay, and wood were chosen not only for durability but for their symbolic resonance and ritual purpose.

African art has also been historically misunderstood because it does not prioritise realism in the European sense. African sculptures, masks, and ritual objects are rarely concerned with photographic likeness. Instead, they emphasise essence, symbolism, hierarchy, and spiritual function. A mask may exaggerate the eyes, distort the face, or abstract the body because it is not meant to represent how a person looks, but what they represent: power, wisdom, transition, protection, or memory. African art is narrative, historical, and spiritual. It tells stories of events, lineages, cosmologies, and moral codes.

Ironically, when European artists began to draw inspiration from African art, those same qualities suddenly became signs of genius. Pablo Picasso’s development of Cubism was directly influenced by African masks and sculptural forms. The abstraction, distortion, and symbolic representation that had been dismissed as “primitive” were reframed as revolutionary when filtered through a European artist. Picasso was celebrated as a visionary, while the African artists whose philosophies shaped his work remained unnamed, uncredited, and historically marginalised.

This pattern mirrors the broader treatment of African spiritual architecture. African shrines were dismissed as small, crude, or insignificant because they did not conform to European expectations of grandeur. Yet they were perfectly suited to African spiritual needs. Development is not universal; it is contextual. African societies developed technologies, belief systems, and artistic traditions aligned with their environments, social structures, and cosmologies. To judge African civilisation by European standards alone is to misunderstand civilisation itself.

In contemporary Africa, sacred sites and ancestral shrines continue to adapt. Some exist alongside churches and mosques. Others are revived by younger generations seeking reconnection with heritage. These shrines are not relics of a forgotten past but living spaces of memory and meaning. They remind us that spirituality does not require spectacle to be profound, and that intimacy with the sacred can be just as powerful as architectural grandeur.

African sacred spaces teach a crucial lesson: civilisation is not measured by size, height, or stone, but by coherence between belief and expression. African spirituality built what it needed, not what it was told to build. And in doing so, it produced systems of worship, art, and philosophy that remain deeply human, grounded, and enduring.