One of the most enduring damages of colonial rule in Africa is not only economic exploitation or political domination, but the artificial borders imposed on the continent, borders that ignored history, culture, and human relationships. These colonial boundaries, drawn with rulers on maps far from Africa, disrupted societies that had existed for centuries and planted the seeds of ethnic tensions that persist today.

Before colonial intervention, African societies were not random or chaotic. Many regions were already well documented by anthropologists, explorers, and historians. These reports identified kingdoms, empires, city-states, and communities grouped along shared ethnic, linguistic, and cultural lines. Political organisation existed in forms that made sense to the people themselves: federations, kingdoms, confederacies, and loosely connected regions bound by trade, ancestry, and belief systems.

However, during the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, these realities were largely ignored. European powers gathered to divide Africa among themselves for economic extraction and administrative convenience. The goal was not stability or cultural coherence, but control. As a result, pre-existing African political and social structures were dismissed, and borders were drawn without regard for kinship, ethnicity, or shared history.

This process split entire peoples across newly created colonies and forced unrelated groups into single political units. Families, clans, and ethnic groups that had lived together for generations suddenly found themselves separated by international borders. At the same time, rival groups with little cultural or historical connection were merged into one country and expected to function as a unified nation.

Nigeria offers a clear example of this disruption. The Yoruba people, who once occupied a continuous cultural and geographical space, were divided by colonial borders. Today, Yoruba communities are found not only in Nigeria, but also in Benin Republic and Togo. Before colonial partition, these people shared language, religion, trade networks, and political institutions. The borders that now separate them are colonial inventions, not reflections of indigenous reality.

The same pattern appears across Africa. The Ewe people span Ghana and Togo. The Somali are spread across Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Djibouti. The Hausa extend across Nigeria and Niger. These divisions fractured identities and weakened collective political power, while simultaneously creating tension within the new states.

Within countries like Nigeria, the consequences have been profound. Multiple ethnic groups with distinct cultures, histories, and worldviews were forced into a single national identity without a shared foundation. Expecting immediate unity under such conditions was unrealistic. Ethnic competition over power, resources, and recognition became inevitable, especially when colonial administrations favoured some groups over others for governance and economic roles.

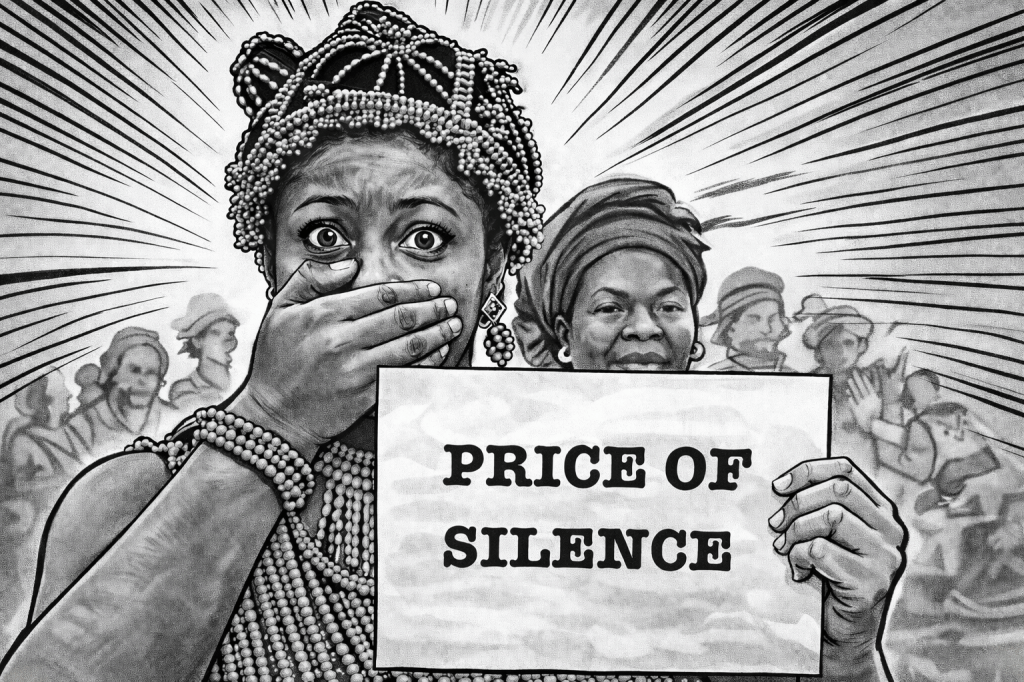

Colonial authorities were fully aware of these risks, but they did not care. Division made rule easier. Fragmented societies were less likely to unite against colonial power, and ethnic rivalry distracted from resistance. Economic interests, access to land, labour, and raw materials, took priority over social cohesion. When independence came, colonial powers withdrew, leaving behind states burdened with unresolved internal contradictions.

Today, many African countries continue to struggle with ethnic tension, separatist movements, and identity-based conflict rooted in these colonial boundaries. In Nigeria, debates around federalism, restructuring, and national unity are inseparable from the reality that many ethnic groups feel little cultural or historical connection to one another. The challenge is not simply political; it is deeply historical.

This does not mean Africa was conflict-free before colonialism. No society is. But conflicts then were governed by indigenous systems of diplomacy, warfare, and reconciliation that understood local realities. Colonial borders dismantled these systems and replaced them with rigid structures that often intensified rather than resolved tensions.

Colonial rule ended decades ago, but its borders remain. And with them remain the problems they created. Understanding this history is essential, not to excuse present failures, but to explain why nation-building in Africa has been uniquely complex. The artificial carving of the continent did not just redraw maps; it reshaped identities, disrupted unity, and created fractures that still define African politics today.

Colonial borders are not just lines on a map. They are living scars.