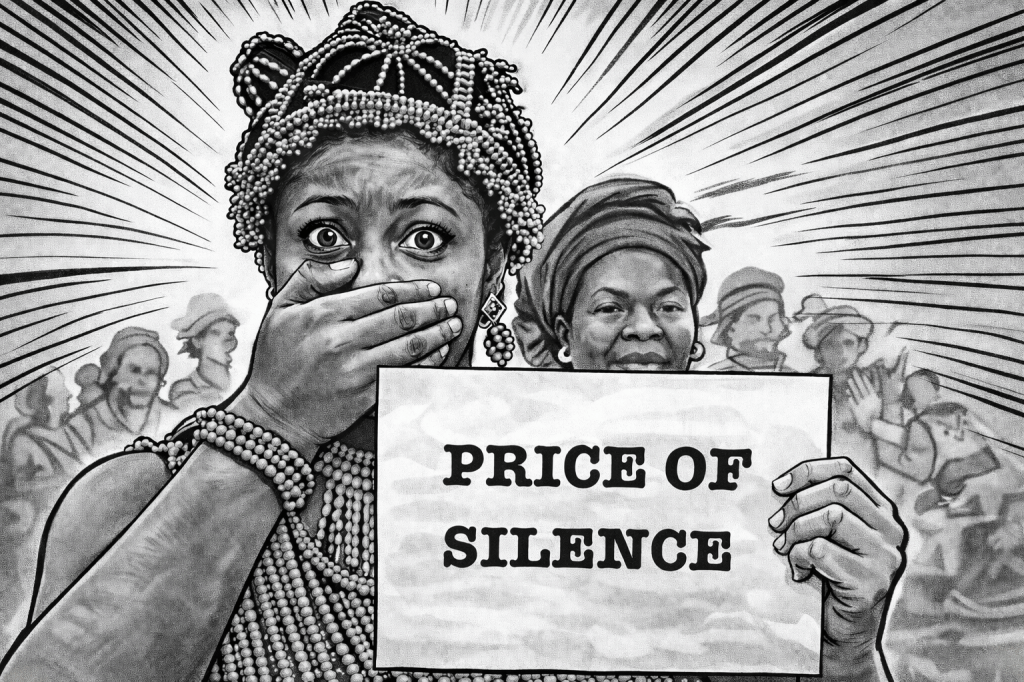

One of the most uncomfortable truths Nigerians rarely confront honestly is how begging has slowly been normalised in public life. What was once associated with extreme hardship or social displacement has, over time, become casual, transactional, and disturbingly acceptable. From streets to offices, from checkpoints to airports, begging has evolved into something more corrosive: entitlement, extortion, and public embarrassment on a national scale.

This culture did not appear overnight. It is the product of economic pressure, weak institutions, and a society that has learned to survive by improvisation rather than structure. But understanding the causes does not excuse the damage it now does, to dignity, to trust, and to Nigeria’s global image.

In many parts of Nigeria, begging is no longer passive. It is aggressive. It is coercive. It often wears a uniform. Travellers know this too well. At airports, officials tasked with security and service routinely turn their positions into opportunities for extortion. Documents are delayed, bags are unnecessarily searched, rules are suddenly “invented,” all to pressure travellers into “settling.” What should be a point of national pride, the first and last impression of the country, has become a site of shame.

This behaviour is not just corrupt; it is humiliating. It signals to the world that Nigeria’s systems cannot function without bribery, and that authority is merely a tool for personal gain. No country can command respect when its institutions beg.

The problem extends beyond officials to everyday social behaviour. Recent global attention, such as during IShowSpeed’s visit to Nigeria, exposed this reality in an unfiltered way. Instead of cultural confidence and hospitality, what many viewers saw was desperation. If people weren’t begging for collaborations, they were begging for money. If not money, then clout. The interaction often lacked boundaries, dignity, or self-awareness. It wasn’t enthusiasm, it was neediness on display.

This matters because moments like these shape perception. Digital platforms do not forget. Millions of people encountered Nigeria through those clips, and what they saw reinforced harmful stereotypes Nigerians themselves complain about. Image is not cosmetic; it is political, economic, and psychological. Countries are judged by how their citizens carry themselves in moments of visibility.

At the root of this issue is a deeper social breakdown. Nigeria has become an environment where survival often requires aggression. To function, many feel they must be louder, tougher, more forceful than the next person. Courtesy is seen as weakness. Order is mistaken for foolishness. Chaos becomes a strategy. In such a space, begging and extortion stop feeling shameful and start feeling practical.

But a society cannot survive long on madness alone.

The normalisation of begging reflects a loss of collective standards. It shows how far Nigeria has drifted from shared ideas of dignity, professionalism, and civic responsibility. When people no longer expect systems to work, they exploit them. When the future feels uncertain, short-term gain overrides long-term reputation.

This is why Nigeria does not just need economic reform or anti-corruption slogans. It needs social restructuring. A reset of values. A re-education around boundaries, service, and self-respect. Institutions must be rebuilt to reward integrity and punish extortion consistently. Public servants must understand that their roles are not opportunities for personal income. And citizens must reject the idea that begging, especially from strangers and visitors is normal behaviour.

Restructuring also means confronting uncomfortable questions: Why is dignity no longer central to public life? Why has hustle replaced honour? Why do Nigerians abroad often behave differently than Nigerians at home? The answers lie in accountability, enforcement, and cultural expectations.

Nigeria is not short of talent, intelligence, or resilience. What it lacks is a social contract that protects dignity. Until begging and extortion are socially unacceptable, not just illegal, the problem will persist.

Fixing this is urgent. Not for foreigners. Not for optics alone. But because a society that loses shame loses direction. And a country that wants respect must first respect itself.