One of the most enduring legacies of colonialism in Africa is not only found in political borders or economic structures, but in the education systems inherited by post-colonial states. In Nigeria, many school rules, disciplinary practices, and ideas of “proper appearance” are direct continuations of colonial education models designed by European missionaries and administrators. Among these is the strict regulation of Black hair, particularly the compulsory barbing of young Nigerian female students’ hair.

Colonial education systems in Nigeria were established largely by Christian missionaries during British rule. These schools were not neutral spaces of learning; they were tools of cultural transformation. European standards of cleanliness, order, and respectability were imposed on African bodies, languages, and identities. Black hair, in its natural state, was often described by missionaries as “untidy,” “bushy,” or “uncivilised.” This perception was rooted in racist beliefs that equated European physical features with superiority and African features with disorder.

As a result, African students, especially girls were required to cut their hair extremely low, sometimes to the skin. This was never a rule applied equally. In Britain, the very same colonial powers allowed young girls and boys to wear their hair freely, long or short, so long as it was clean. The issue was never hygiene; it was racialised control.

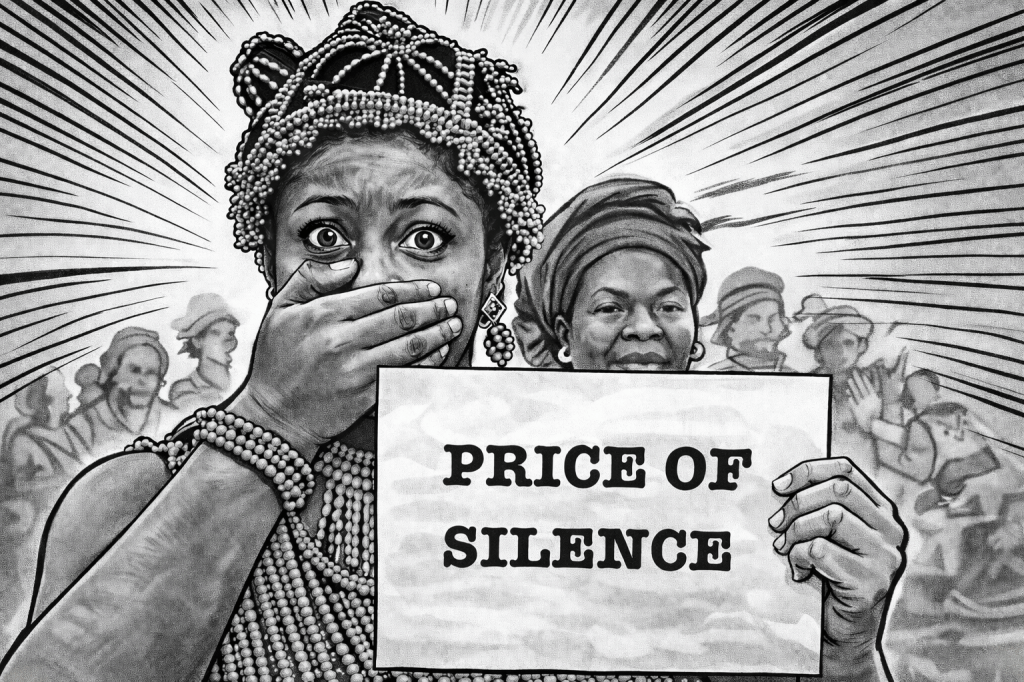

Decades after independence, this colonial construct remains deeply embedded in Nigerian schools. Female students are still punished for having hair considered “too bushy,” “too full,” or “too natural.” Some schools equate natural Afro-textured hair with indiscipline, rebellion, or moral failure. This practice persists not because it serves educational development, but because colonial ideas were never fully dismantled from the school system.

The consequences for students are profound. For young girls, compulsory hair cutting often leads to humiliation, lowered self-esteem, and body shame. It teaches them, from a very early age, that their natural appearance is unacceptable and must be controlled to fit an imposed standard. This internalised rejection of Black identity can affect confidence, participation in school, and long-term self-worth.

Psychologically, these policies send a damaging message: that African hair must be suppressed to be respectable. Socially, they reinforce gendered control over girls’ bodies, disproportionately targeting female students while male students often face far less scrutiny. Culturally, they contribute to the erasure of African aesthetics and self-expression in spaces meant to nurture growth and learning.

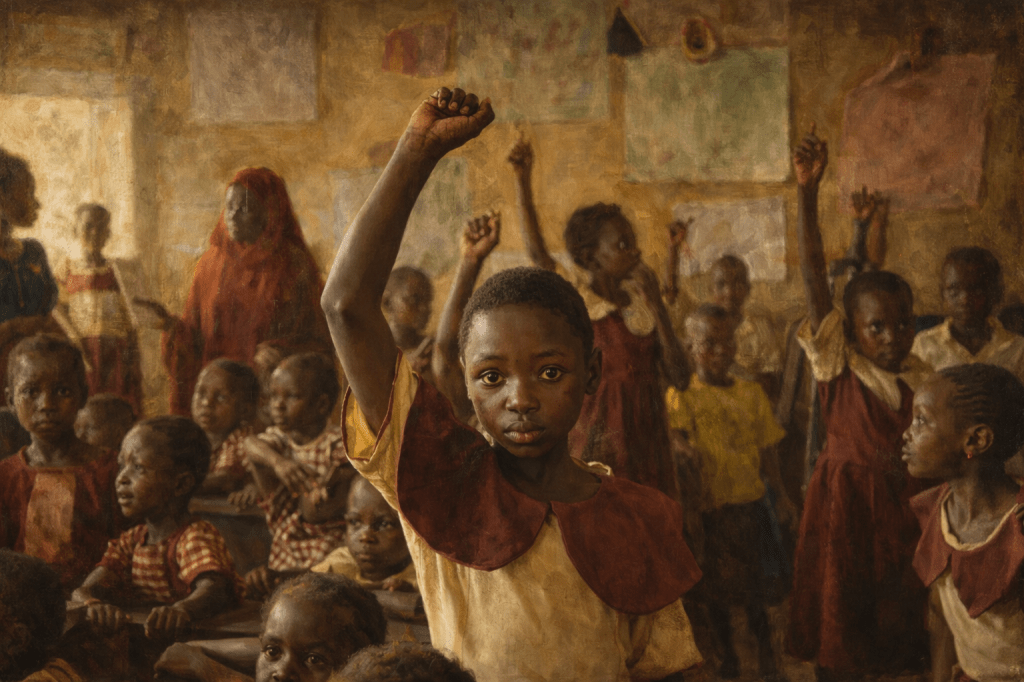

Allowing Nigerian female students and students across Sub-Saharan Africa to keep their hair, however long they choose, is not a threat to discipline or education. On the contrary, it affirms identity, boosts confidence, and fosters self-acceptance. When students feel respected and seen, they are more likely to engage positively with learning environments. Education should develop the mind, not police the body.

Globally, there is growing recognition that discrimination based on hair texture and style is a form of racial bias. African schools must also confront this reality. Maintaining hygiene and safety does not require enforcing colonial beauty standards. Clean, well-kept hair can exist in many forms, including natural Afro hair, braids, twists, and locs.

Decolonising education means more than changing curricula; it requires dismantling inherited beliefs that still shape how African children are treated. The continued punishment of young Black girls for their natural hair is a reminder that colonialism did not end, it adapted.

Supporting Nigerian female students’ right to wear their hair freely is an act of cultural reclamation, psychological protection, and educational justice. African classrooms should be spaces where children are taught to value who they are, not trained to reject themselves.