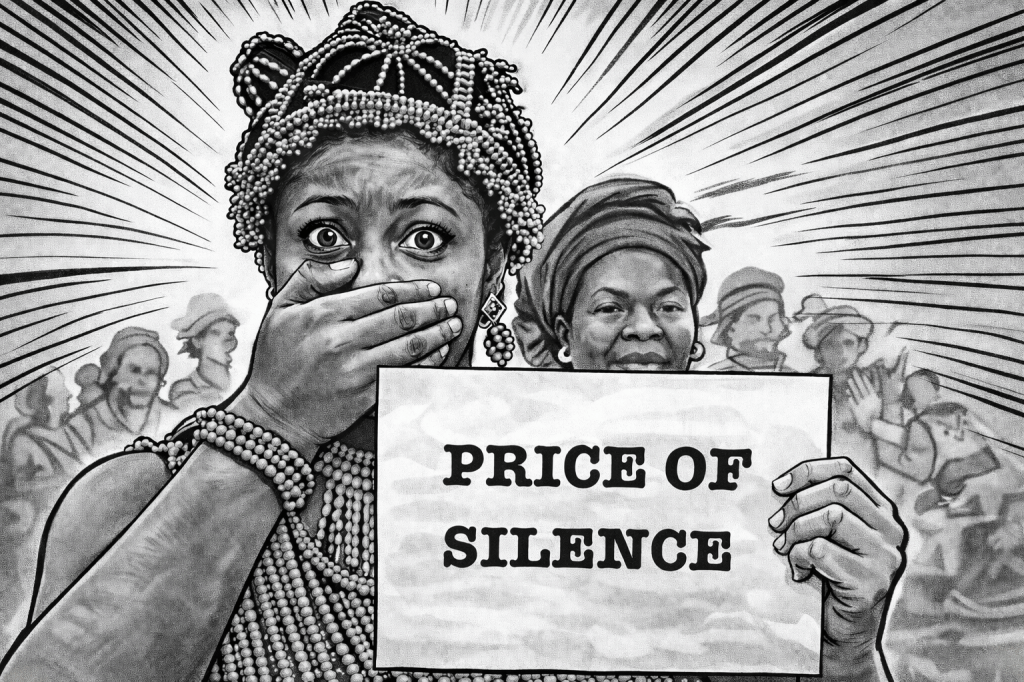

Pre-colonial Nigerian history did not begin with European contact, yet much of what is widely accepted today was filtered, reshaped, and in some cases distorted through the lenses of early colonial writers. These writers, often Africans educated under missionary systems or Europeans documenting societies for imperial interests, became the gatekeepers of history. Their accounts, though valuable, were never neutral. They were shaped by personal origin, political alignment, and the broader colonial agenda of classification and control.

One of the most influential figures in Yoruba historiography is Samuel Johnson, whose work has for decades been treated as a foundational text. While Johnson’s contributions are undeniable, it is increasingly clear that his position, background, and loyalties influenced the way history was framed. Coming from Oyo, his narratives often elevated Oyo’s political and cultural importance, sometimes at the expense of other Yoruba kingdoms. Power dynamics, military reach, and cultural influence were emphasised in ways that reinforced Oyo’s centrality, while other regions were mentioned briefly, subordinated, or contextualised only in relation to Oyo’s story.

This pattern was not unique to Johnson. Many early African historians worked under colonial patronage or missionary influence, and their writings often aligned with European expectations of hierarchy, centralisation, and dominance. Kingdoms that fit colonial ideas of empire and expansion were amplified, while those that operated through different political systems such as federations, spiritual authority, or trade networks were marginalised. Over time, these selective narratives hardened into “official history.”

What makes this distortion more evident today is the rediscovery of earlier anthropological and travel records written before full colonial consolidation. Explorers, traders, and anthropologists who travelled through the region prior to formal colonial rule documented a far more complex and balanced landscape of power. Their journals describe multiple thriving cities, sophisticated political systems, and regional powers that coexisted without a single dominant centre.

For example, in an 1857 journal, T. J. Bowen described Owo in present-day Ondo State as a large and powerful city, bigger than many other Yoruba cities of the time, with considerable influence over surrounding regions. This directly challenges later narratives that reduced Owo to a peripheral role in Yoruba history. Similar passing references exist for other kingdoms whose histories were not fully explored because they did not align with colonial or missionary priorities.

These earlier accounts were not necessarily more detailed, but they were closer in time to the societies they described and less shaped by the need to organise Africa into administratively convenient hierarchies. Unfortunately, many of these records were later overlooked in favour of colonial-era histories that were more comprehensive, widely published, and institutionally endorsed.

With the advent of the internet, digitised archives, and renewed interest in indigenous history, scholars and the public are beginning to question long-held assumptions. Oral traditions, archaeological findings, and cross-referencing of early travel journals are revealing that some well-documented histories were not false, but exaggerated in ways that elevated certain groups while diminishing others. This does not invalidate those histories, but it does demand correction and balance.

History is not a competition of greatness, but a record of existence. Pre-colonial Nigeria was not organised around a single centre of power. It was a mosaic of kingdoms, cities, and communities, each with its own form of governance, influence, and legacy. Some dominated militarily, others economically, spiritually, or culturally. Reducing this complexity to a single narrative impoverishes our understanding of the past.

There is still much work to be done. Many kingdoms remain under-documented, their histories preserved mainly through oral tradition and scattered references. These histories deserve rigorous research, proper documentation, and equal recognition. Correcting historical imbalance is not about diminishing any group, but about restoring accuracy and dignity to all.

As access to information grows, so does the responsibility to revisit what we think we know. Nigerian history, like African history as a whole, must be continually re-examined, not through colonial hierarchies, but through evidence, plurality, and truth. Only then can credit be given where it is due, and history told as it truly was—complex, diverse, and shared.