The rise of Pan-African digital identity has become one of the defining features of the 21st-century African online presence. Across social media platforms, African and African-descended users are increasingly claiming a shared identity, celebrating African culture, history, and aesthetics in ways that blur geographic and national boundaries. The meaning of “African” online often differs significantly from its reality offline. Online, Africa is frequently imagined as a unified, singular entity, a canvas for cultural pride and Pan-African aspirations. Offline, however, the continent is a complex tapestry of over 50 countries, thousands of ethnic groups, countless languages, and a history filled with both cooperation and conflict.

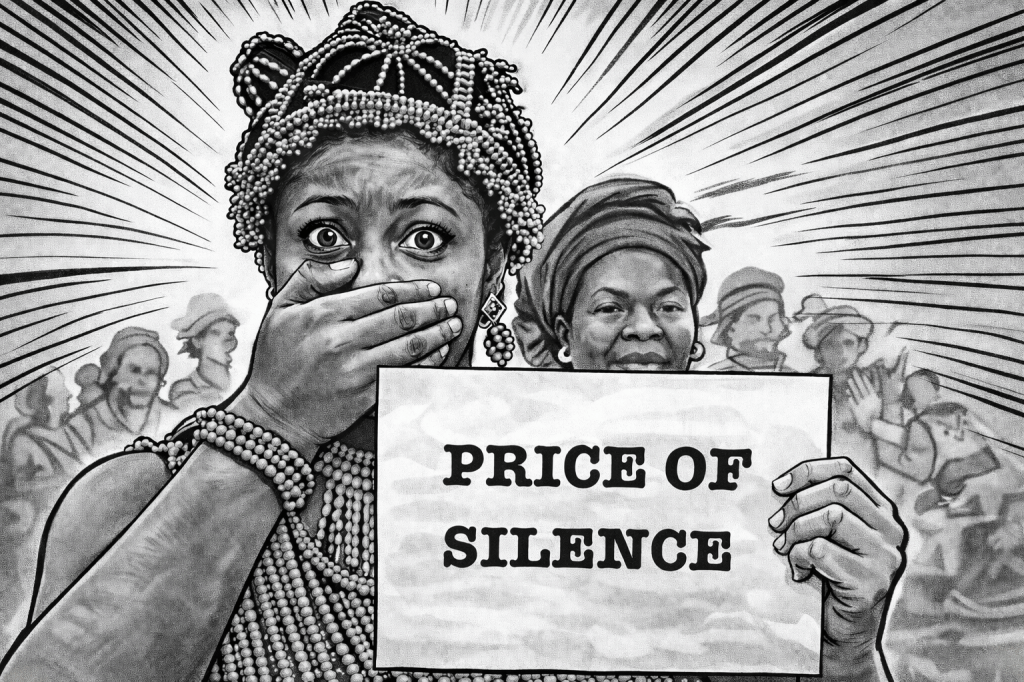

This divergence becomes most visible when African Americans engage with Pan-African ideas. Many African Americans who advocate most fervently for continental unity often do so with limited understanding of Africa’s realities. In their pursuit of unity, they tend to overlook the deeply entrenched cultural, ethnic, and political differences that shape the continent. While their intentions may be rooted in solidarity, their approach frequently mirrors the paternalistic mindset of historical missionaries who once judged African societies through a European lens, condemning traditional practices and claiming to bring civilization without genuine understanding.

Pan-Africanism in its idealized form promises a continent connected not just by history but by shared values, economic cooperation, and political solidarity. Yet this vision often clashes with the lived experiences of Africans today. Tribal and ethnic loyalties remain strong, and religious divisions run deep. Historical animosities and modern geopolitical tensions compound these divides. The xenophobic attacks against migrants in South Africa, for example, reveal the fragile and contested nature of inter-African relationships. Any movement toward continental unity must first grapple with these underlying realities. Surface-level solidarity is insufficient.

Moreover, African Americans promoting Pan-Africanism online sometimes do so with a savior complex, unconsciously adopting the same posture that once framed Europeans’ engagement with Africa. Debates erupt on social media fueled by misconceptions or idealizations, often amplifying divisions rather than building bridges. The result is a version of Pan-Africanism that resonates more with diaspora imagination than with the nuanced realities on the continent itself.

For Pan-Africanism to gain genuine traction, it must begin at the grassroots level within Africa, taking into account local histories, cultural practices, and political realities. Unity cannot be imposed externally or imagined solely through a digital lens. It requires dialogue, mutual understanding, and careful navigation of the continent’s inherent diversity. Until then, Pan-Africanism risks remaining an aspirational concept for the diaspora rather than a movement supported by those who live its complexities every day.