Cancel culture in African contexts, particularly in Nigeria, raises difficult questions about justice, accountability, and the uncritical borrowing of social frameworks developed elsewhere. Over the years, the world has watched American celebrities face public “cancellation” for actions ranging from criminal behavior to offensive speech made early in their careers. Figures like R. Kelly, DaBaby, Chris Brown, Kanye West, and others have faced varying degrees of social, commercial, and institutional consequences. In the American context, cancel culture carries weight because it is often backed by grassroots mobilization, media pressure, corporate withdrawal, and, in some cases, legal action. Whether one agrees with it or not, cancellation there functions as a social mechanism with real consequences.

As this culture migrated into Nigerian social media spaces, it arrived largely as a borrowed framework, one that looks familiar on the surface but lacks the structural integrity that gives it meaning in its original context. In Nigeria, calls to “cancel” celebrities trend loudly online, but rarely translate into sustained consequences. Endorsements remain intact, concerts sell out, and public affection quickly returns. What emerges is not accountability, but performance: outrage without follow-through.

A key reason for this failure is selective solidarity. Nigerian audiences often extend unconditional loyalty to their favorites, regardless of repeated misconduct. Burna Boy offers a clear example. Despite a pattern of public disrespect toward fans and controversies surrounding his behavior, his career trajectory remains largely unaffected. When a “Cancel Burna Boy” protest briefly gained traction on social media after he disrespected a fan during a performance, it quickly fizzled out. Today, he continues to headline shows and secure major endorsements. The outrage existed, but the collective will to enforce consequences did not.

This pattern repeats itself across the entertainment industry. Davido is frequently shielded by an almost mythic loyalty from fans, evident in comments such as “Davido can do no wrong in my eyes.” Even when questionable behavior is acknowledged, it is excused, reframed, or dismissed as irrelevant. Meanwhile, another celebrity, less popular or less protected may be aggressively “cancelled” for the same behavior or even less. This inconsistency exposes a core flaw: cancellation in Nigeria is rarely guided by shared moral standards. It is driven by fandom, tribalism, class loyalties, and online mob psychology.

A disturbing example of this selective accountability is the case of Darlington Okoye, known as Speed Darlington. During an Instagram Live session, he publicly claimed to have had sexual contact with a minor, sparking brief outrage online. Yet, as with many such cases in Nigeria, the backlash was short-lived. No visible investigation or legal action followed, and while the issue was still trending, he reportedly left the country and relocated to the United States.

When Speed Darlington later returned to Nigeria, he resumed public life with little resistance, continuing to receive fan support as if the incident had never occurred. The allegation, one involving a minor, quietly disappeared from public discourse. This case highlights the emptiness of cancel culture in Nigeria, where even the most serious claims fail to produce sustained accountability, and popularity often outweighs justice.

As a result, cancel culture in Nigeria often resembles vendetta rather than justice. Groups mobilize not because a line has been morally crossed, but because a celebrity has offended their community, challenged their favorite, or disrupted existing power hierarchies. In some cases, a public figure is targeted simply for having conflict with a more beloved celebrity, even when the so-called favorite was the aggressor. Accountability becomes secondary to allegiance.

This dynamic is also shaped by deeper structural realities. Unlike the American entertainment ecosystem, Nigeria lacks strong institutions that connect public outrage to material consequences. There are weak unions, limited consumer activism, inconsistent brand ethics, and little expectation that corporations should respond to public moral pressure. Social media becomes the courtroom, the judge, and the executioner—but only temporarily. Once the trend fades, so does the punishment.

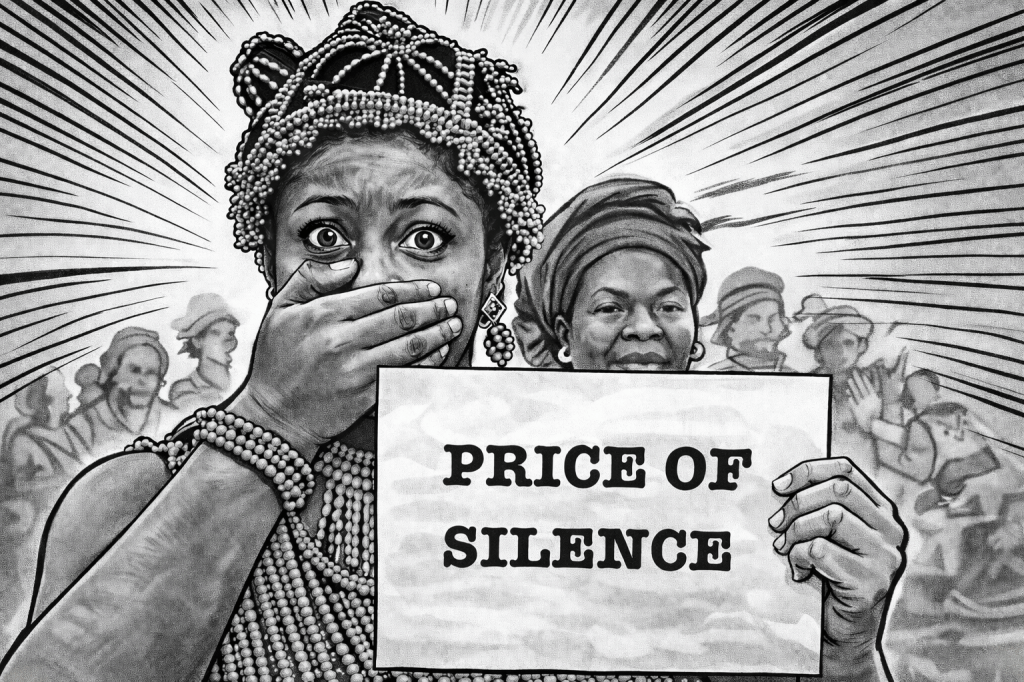

More troubling is how this hollow version of cancel culture distracts from more urgent forms of accountability. While celebrities trend for scandals, systemic issues, state violence, corruption, labor exploitation, gender-based violence, rarely sustain the same level of outrage or collective action. The energy spent “cancelling” individuals is rarely redirected toward challenging institutions that cause far greater harm.

In this sense, cancel culture in Nigeria is less about justice and more about spectacle. It borrows the language of accountability without building the structures needed to support it. Until there is a shared ethical baseline—one that applies equally regardless of fame, fandom, or personal loyalty—cancellation will remain inconsistent, selective, and ultimately ineffective.

What Nigeria is witnessing is not cancel culture in its functional sense, but a distorted echo of it: loud, emotional, deeply unequal, and largely symbolic. Without integrity, cancellation becomes just another tool for social punishment, not moral reckoning.