In many societies, adulthood is judged by distance. Not emotional maturity. Not financial stability. Not character. Distance. How far you live from your parents becomes the visible proof that you have “made it.” By the time someone reaches their late twenties or thirties, the question begins to echo louder than anything else. Why are you still at home?

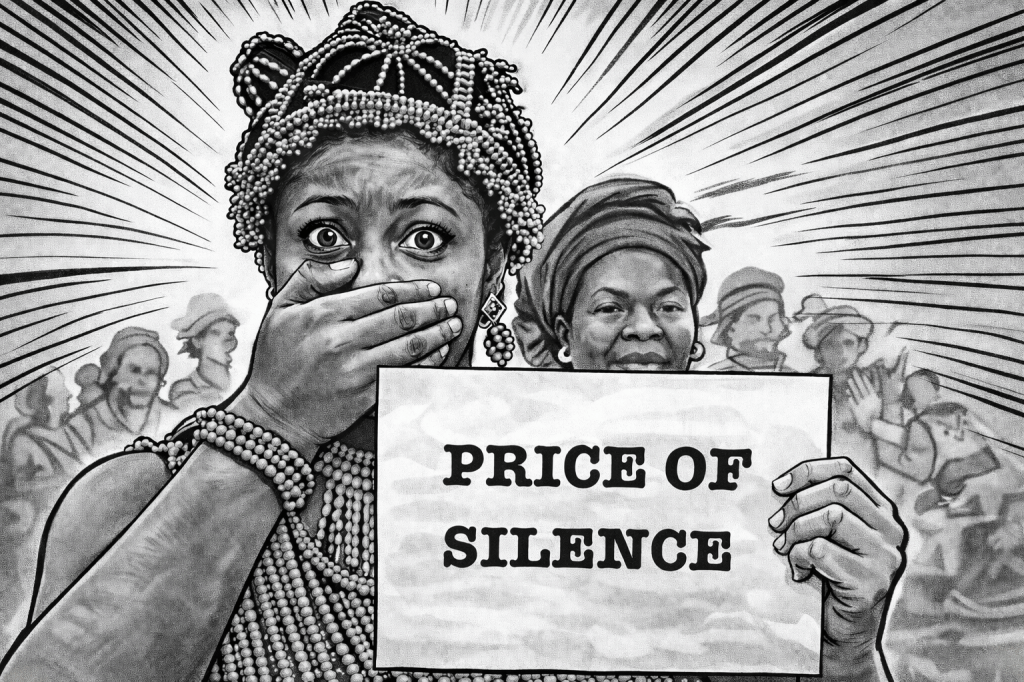

Yet the pressure to leave home is not evenly distributed. It falls most heavily on those from poor and working class backgrounds. In lower income communities, there is often an invisible deadline attached to independence. By a certain age, you are expected to move out, no matter your financial reality. Staying beyond that age can attract subtle mockery, open criticism, or silent disappointment. Independence becomes less about readiness and more about performance.

Meanwhile, in wealthier families, the narrative can look very different. Children are often encouraged to remain within the family estate for as long as possible. In large homes with multiple buildings or expansive compounds, adult sons may marry and continue living within the family property. Some even begin raising their own families there. It is seen as continuity, legacy, or strategic positioning rather than dependency. The same act that is condemned in poorer communities is reframed as wisdom in affluent ones.

This contrast reveals that the issue is rarely about age. It is about class.

For families with limited resources, keeping adult children at home can feel financially heavy. Parents who are already stretched thin may push their children to move out not because they are ashamed of them, but because survival demands it. At the same time, many young adults from poor backgrounds internalize a cultural script that equates renting a small apartment with success. Even if that apartment consumes most of their income, it signals adulthood. The optics matter. Among peers, posting house keys and new living spaces carries social currency. Quietly struggling behind closed doors is preferable to being perceived as stagnant.

There is also a deeply rooted age expectation in many Nigerian communities. Once you cross a certain threshold, remaining at home is interpreted as failure. The judgment can be harsh and unforgiving. Ironically, those who rush out early are often the ones battling rent anxiety, unstable living conditions, and constant financial stress.

What is rarely acknowledged is that staying at home, when the environment is supportive, can be a powerful economic strategy. Without the immediate burden of rent and high food costs, a young adult can save aggressively. The money that would have disappeared into monthly survival expenses can be redirected into business capital, professional certifications, investments, or long term financial planning. Instead of living paycheck to paycheck, they can build a cushion. Instead of scrambling for the next rent cycle, they can think beyond the month.

Living at home can also create space for intentional self development. There is room to take calculated risks, to experiment with entrepreneurship, to pivot careers without the constant fear of eviction. The psychological relief of not worrying about shelter every month can foster creativity and strategic thinking. For many, it becomes a season of preparation rather than stagnation.

Family bonds can deepen during this time as well. Multigenerational living is not abnormal globally. In many cultures, it is the norm. Shared resources reduce overall expenses and strengthen collective resilience. A household that pools finances can often move further together than individuals struggling separately.

On the other hand, leaving too early when one is not financially prepared can quietly delay progress. High rent can consume the majority of income, leaving little room for savings. Career decisions may be driven by urgency rather than alignment. Business ideas may be abandoned because survival takes priority. Some move into unsafe neighborhoods or substandard housing simply to prove independence. The pressure to appear successful can lead to debt, burnout, and emotional isolation. And when circumstances force a return home, the shame can feel heavier than if they had stayed strategically in the first place.

The truth is that independence should not be measured by how quickly one leaves home, but by how prepared one is to sustain themselves without constant instability. Living alone while drowning in financial pressure is not necessarily more mature than living at home while building capital and developing oneself intentionally.

The stigma attached to staying at home in one’s late twenties or thirties often reveals more about societal insecurity than personal failure. Wealthier families understand that consolidation of resources can accelerate generational growth. Poorer communities sometimes push separation prematurely in pursuit of pride, even when the economics do not support it.

Perhaps the real question is not why someone is still living at home, but what they are doing with the opportunity. If the season is being used to save, invest, learn, and prepare, it may be one of the most strategic decisions a young adult can make. Independence is not a race. It is a responsibility. And responsibility is best carried when one is ready, not when one is pressured.